New cell atlas reveals biological secrets of the mouse lemur – and its close link to human health

‘Tabula Microcebus’ cell atlas is an unprecedented, data-rich tool to explore health, disease, and evolution

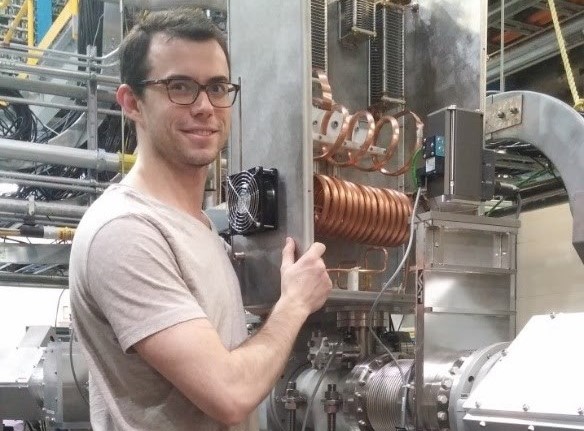

Cote working at TRIUMF, Canada’s national particle accelerator laboratory, in 2017.

Editor’s note: Andrew Cote, a recent alumnus of Chan Zuckerberg Biohub’s Bioengineering Platform team, originally published a version of this essay at Medium.

Now that the COVID-19 pandemic is winding down, with vaccination rates increasing across the world and our lives regaining some semblance of normality, I have been reflecting on my time over the last two years working at a nonprofit involved in infectious disease research, and some of the lessons taken away from it.

Before joining the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, I had spent the previous few years working in accelerator physics designing radio-frequency structures to accelerate beams of particles at close to the speed of light.

Radio-frequency engineering was fun, and exciting; it challenged my knowledge of physics and brought me into close contact with some of the largest, most complicated machines on the planet. It was a boyhood dream come true. But the further I looked into the world of national labs and the big-budget physics projects of the Department of Energy, the more I could not help but ask what tangible impact this work would have on the world around me, on people’s lives? What was the opportunity cost of working on things I thought were “cool” instead of impactful?

Asking that question, and not finding a satisfying answer, motivated me to join the Bioengineering team at CZ Biohub. Their pitch was simple: we’re building open-source, low-cost research instruments to enable pathogen discovery and analysis in the developing world. In October 2019, I could think of few things more impactful that an engineer could do with their time.

A couple months later, the pandemic started. It started slowly, in China, on news reports, and I recall colleagues sharing the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard in the company Slack, discussing the spread of the virus; the cruise ships; cases in Seattle, Florida, Italy.

We were in amazement at China building a hospital in a week, then in terror as they welded buildings shut and blocked highways, and felt horror at seeing the trucks full of body bags in southern Europe. And then the first cases appeared in San Francisco. We saw helicopters flying overhead bringing patients to the isolation unit at one of UCSF’s hospitals; a Biohub MD/PhD Investigator came into the lunchroom, breathless, discussing the first few cases in that ward.

On March 18th, 2020, several family members called me, imploring me to return to Canada, where I’m from. “They’re closing the borders,” they said. I felt fear, and anxiety — would this be like Hurricane Katrina? Would civil society maintain itself in America, or would we be reduced to our worst selves, looting, hoarding, and witnessing the breakdown of law and order?

I recall several conference calls with scientists, doctors, ICU nurses, and engineers, both in my hometown of Vancouver, British Columbia, and in the Bay Area. The projections were grim. ICU bed capacity would be surpassed, ventilators would be in short supply. People would die in hospital parking lots for lack of treatment.

On that same day, when I got in the Biohub elevator on my way home, Joe DeRisi, co-president of the Biohub, got in with me. I expressed my concern for what was to come, and asked what we could do. His response was inspiring. “This is our Super Bowl,” he said; this was our moment to shine, to work hard, to leverage our skills, technology, and talents to rise to the occasion.

And rise we did. The leadership was inspiring, the colleagues around me, amazing. They rose to the challenge, and I did my best to tag along. There was only one purpose in life: to work, to design, to build.

Volunteers from UC San Francisco staffing CZ Biohub’s CLIAhub COVID-19 testing lab in April, 2020. (Photo by J. MacGregor, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative)

My contribution was to design and fabricate “bartender bots,” devices that would automatically fill a tray of 96 nasal swab sample tubes with DNA/RNA Shield, a reagent that inactivates the virus while preserving its RNA for qPCR testing. This would protect the hundred or so volunteers as they handled sample tubes obtained from various California counties, volunteers who selflessly joined the Biohub’s “CLIAhub” to operate the first 24-hour-turnaround, large-scale testing and analysis clinic in the Bay Area.

CZ Biohub–designed bartender bots were soon deployed at similar labs at Berkeley and Stanford, and ultimately these devices prepped more than 250,000 COVID sample tubes. But the work was not done yet. The Bioengineering team also developed, in fairly short order, a simple digital pressure alarm that could detect irregular breathing, over-pressure, or under-pressure in off-the-shelf mechanical ventilators that could be pulled from U.S. Army reserves and put into use at the San Francisco VA Medical Center.

We consulted with doctors, pulmonary experts, and ICU nurses on the features and requirements needed to make a useful, and potentially lifesaving, device that could interface with aging FDA-approved ventilators that lacked the modern electronics and digital interface of those currently in use in hospitals. Fortunately, these never needed to be put into operation, though we did ship 25 units to the VA hospital just in case.

Developing, designing, and engineering tools for both clinical lab testing and hospital patient care in the midst of a global pandemic will always remain a defining moment in my career. I was fortunate to be at an organization like CZ Biohub that was nimble enough to respond to the call to arms, and fortunate to have leaders who acted quickly and decisively to target the point of maximum leverage and to address serious testing shortfalls in the Bay Area.

Most of all, I was grateful to be part of an organization like the Biohub that had a genuine esprit de corps, the capacity to deliver on its promises, and the willingness to take a risk on a former radio-frequency engineer who aspired to change directions and make an impact on global health.

Afterward I worked hard to not just understand how I could contribute as an engineer in the organization, but to better understand how modern-day science works on the “boots on the ground” level. What workflows of scientists, researchers, and lab operations could be helped or hindered by engineering decision-making? What was the unique insight I could contribute as someone with a different perspective and background, an outsider in the lab who sought to be useful in any way I could?

I’m a firm believer that biotech has the potential to radically transform society over the next few decades, just as digital information technology and the Internet have done. Now that I’ve moved on from the Biohub to start my own company, Eta.bio, my goal will remain the same: to understand how I can enable those at the forefront of scientific inquiry to ask bold questions, yield insightful results, collaborate, and communicate their findings to the outside world.

In some ways, it’s the Wild West out there when it comes to how life science gets done in practice, with huge opportunities for innovation and improvement in the day-to-day life of researchers. Oddly enough, my goal is still to accelerate, not beams of protons or radioisotopes, but the process of discovery that drives forward our understanding of biology, and by extension, ourselves.

‘Tabula Microcebus’ cell atlas is an unprecedented, data-rich tool to explore health, disease, and evolution

Learn More

Ensuring all Americans have trust in and access to healthcare is a national challenge. In Montgomery, leaders of the Get Out the Vaccine initiative are working...

Learn More

Meet our new international grantees and discover how they bring new perspectives to the Rare As One Network to address the global challenges of rare disease

Learn More

Stay up-to-date on the latest news, publications, competitions, and stories from CZ Biohub.

Cookies and JavaScript are required to access this form.